“There’s no freedom quite like the freedom of being constantly underestimated.”

At the turn of the 19th century, human flight continued to elude civilization. There were experiments, blueprints, and myths surrounding flight from Icarus to Leonardo da Vinci. But no one had figured out how to master human flight. During the late 1800s, this challenge consumed many of the era’s best scientists and engineers—Sir Hiram Maxim, Alexander Graham Bell, Thomas Edison, Samuel Langley, and the Smithsonian Institution, to name a few.

Meanwhile, Wilbur and Orville Wright ran a bicycle shop in Dayton, Ohio, designing, repairing, and selling bicycles. But they, too, had grown fascinated with the challenge of flight.

In 1899, Wilbur wrote to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington requesting documents on the subject of human flight. The Smithsonian passed along a stack of pamphlets on aviation, and the brothers started studying. Later that summer, above their bicycle shop on West Third Street, they began building their first aircraft—a glider with double wings spanning five feet made of split bamboo and paper.

Unlimited resources don’t equal better results

No one took the Wright brothers seriously, at least not yet. They were just two entrepreneurs building bicycles and living in the backwaters of Ohio. All the innovation was happening on the East Coast and in major European cities like Paris and London, led by well-funded scientists and engineers. But despite the resource advantage and the money being thrown at the problem, success remained elusive for those pursuing flight.

Sir Hiram Maxim, the inventor of the machine gun, spent $100,000 on a giant, steam-powered flying machine, which turned out to be a spectacular failure, crashing immediately upon take off.

But Samuel Langley was the most notable frontrunner in the race to human flight. Langley was the head of the Smithsonian, an eminent astronomer, and one of the most well-respected scientists in the United States. He was years ahead of the Wright brothers, and his experiments were backed by government funding. Langley held a tremendous advantage in his access to resources—both in terms of capital and information.

But with nearly unlimited resources, the stakes were higher and the pressure greater for Langley. After years of secretive work, he revealed what he called an “aerodome”—a steam-powered flying machine with V-shaped wings that gave it the appearance of a “monstrous dragonfly.”

The aerodrome cost $50,000 in public money—grants from the Smithsonian and the U.S. War Department. Langley, Graham Bell, and others contributed another $20,000 of their own money. But the device could only “fly” in calm weather where the wind wasn’t a factor, which was as practical as building a boat unable to navigate waves.

When it came time for a public demonstration, the aerodome was loaded onto the roof of a houseboat in the Potomac River near Quantico, Virginia, before being launched into the sky by catapult. Almost immediately, the wings crumbled, and the airship spun backward and plunged into the Potomac just 20 feet from where it had been launched. Langley’s efforts had taken more than eight years and failed to produce any meaningful progress.

Resourcefulness wins out

During this same time, the Wright brothers were relentless in their efforts. Wilbur and Orville ran the bicycle shop by day and worked each night on their investigations into flight. After identifying the ideal place to test their first glider in Kitty Hawk on the desolate Outer Banks of North Carolina with windy conditions and sand hills for safe landings, they began their experiments. The first full-sized glider they brought to Kitty Hawk had a wingspan of 18 feet and cost just $15.

Wilbur and Orville would return to Kitty Hawk every fall for the next four years to run experiments and test new iterations. As competition took notice and patrons reached out to help back the Wright brothers financially, Wilbur and Orville politely refused. They kept the bicycle shop open to help pay for their experiments and bootstrap their exploration into flight. And during frigid midwest winters in Dayton when it was too cold for cycling, they sharpened ice skates at the shop for 15 cents each to generate additional income.

In their early, self-funded experiments, Wilbur and Orville learned that many of the widely accepted calculations and tables relating to foundational concepts in aviation, like lift and drag, prepared by authorities were fundamentally wrong and couldn’t be trusted. To improve the accuracy of their calculations, the Wright brothers built a small wind tunnel upstairs in their bicycle shop—a wooden box roughly six feet long with a fan mounted at one end. Over the next few months, they tested 38 different wing surfaces at different angles and wind speeds.

After dialing in their own calculations, by the fall of 1902, they had completed a third iteration of their glider. And in just two months in Kitty Hawk, the Wright brothers had completed a thousand glides and solved the last remaining control problems. With relentless focus, data-driven experimentation, and thoughtful iterations, they had built a machine that could fly, and in the process, honed the skills to pilot it. The next step would be to add a motor. And by the following winter, Wilbur would complete the first powered flight in human history, covering a quarter mile in 59 seconds.

In contrast to Langley’s $70,000 failed effort, the Wright brother’s expenses over four years, including materials and travel, totaled less than $1,000—all paid for by the proceeds from their bicycle shop in Dayton. Their competitors, with seventy times the amount of resources, couldn’t keep pace.

Despite Wilbur and Orville both lacking formal education or influential connections and living outside of the intellectual centers of the world, they were the first to solve the challenge of controlled human flight. They were both driven by and dedicated to solving the problem. Not because they were supposed to. And not because of the prestige it would garner. But because it was an inspiring challenge that they both felt a connection to.

Less to lose

The Wright brothers were outsiders. And as outsiders, they could think for themselves while competitors imitated each other’s devices and worked from flawed formulas. The Wright brothers faced less external pressure, which crippled even the best scientists, like Langley. And this freed them to experiment and find their own way. No one was expecting anything from them, and that was just fine by them. They had less to lose. Their competitors had reputations to protect.

It’s true that in specific industries like politics, you must be an insider to enact real change. But for the rest of us building, leading, and creating something of our own, it’s not always the advantage we believe it to be.

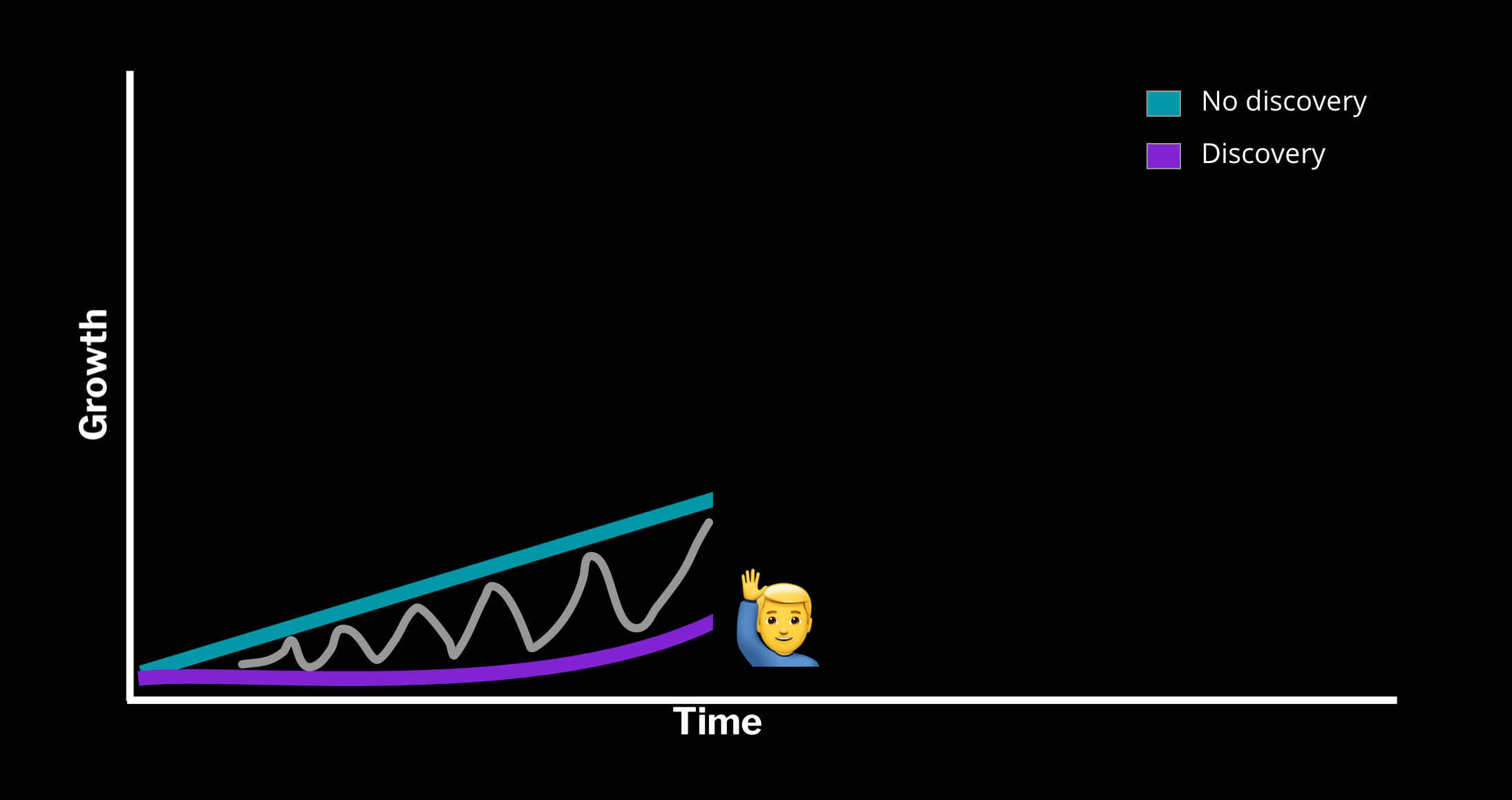

As an insider in your industry, your worldview begins to narrow. And most of your energy becomes directed toward preserving your ability to think for yourself and avoid getting sucked into what everyone else is thinking. And when you have access to unlimited resources, it restricts your creativity. You’re no longer forced to effectively prioritize or consider different vantage points that allow you to do more with less. You become entrenched in what everyone else is doing, and it’s difficult to see beyond that.

Many times, the inside track with well-funded, resource-rich, established companies, teams, and figureheads, is where the least amount of work gets done. They grow too comfortable, lack focus, or take on initiatives for the wrong reasons, like ego or fear, resulting in a fragile, reactive approach. They’re playing not to lose, which is very different from the flexibility and boldness that you play with to win. That’s why new startups come along and disrupt big companies each day. They have less to lose.

Embracing the role of an outsider can work to your advantage. You face less pressure and fewer distractions. And this helps preserve both your ability to think for yourself and the energy you can dedicate to building. If you become too enmeshed in what everyone else is doing, it can be difficult to step back and return to first principles.

The Wright brothers leveraged available knowledge, but they questioned and validated every assumption they came across. They focused on the problem. They focused on building. They focused on their own experiments. And as outsiders, they were provided an advantage in that they didn’t have to deal with the same level of obligations or distractions someone like Samuel Langley faced. They could operate with greater flexibility and were free to do the work.

As an outsider, you face greater odds. But those odds act as a natural filter for work you don’t find all that meaningful. If you aren’t motivated by what you’re doing and lack a deeper connection to your work, you will get absolutely crushed. There’s no faking it. Whereas on the inside, you can float by without making hard decisions or determining if you’re doing it for the right reasons.

Bootstrap your idea into reality

This was the difference between the Wright brothers and Langley. Flight was a quest the Wright brothers found personal meaning in. They weren’t motivated by fame, reputation, or external validation. The reward was the challenge and committing themselves to a cause they cared about. And just as importantly, they embraced their role as outsiders, bootstrapping the whole thing and avoiding the obligations associated with taking on outside capital.

You don’t need to secure a record deal, an agent, or get into Y-Combinator to create a successful album, book, or company. Andy Weir self-published The Martian, which sold 35,000 copies in its first three months and later grossed over $630 million worldwide in its film adaptation. After getting rejected by every major label in town, Jay-Z started his own label—Roc-A-Fella Records—to release his first record, Reasonable Doubt, selling more than 420,000 units. Yvon Chouinard started what would grow into Patagonia after buying a used coal-fired forge from a local junkyard, teaching himself blacksmithing, and forging climbing gear for his friends. Patagonia didn’t take a dime of outside capital for its first 20 years and has sustained success over five decades, now generating well over $1 billion in annual revenue.

We live in an era where it’s easier than ever to bootstrap our own ideas and embrace the outside track. You can launch your own startup as a side hustle and access thousands of low-cost tools to run your business without diluting your ownership. You can record your own album and distribute it independently without handing over the rights to labels and publishers. And all of this can work to your advantage.

When you avoid taking on external resources and unnecessary obligations, you simplify decision-making and preserve the integrity of what you’re trying to build. There’s less noise influencing your work. And it helps you to avoid getting caught up in false goals and virtue signaling.

Seek accomplishment in the work, not external validation

Far too many people conflate external validation with accomplishment. But raising a Series-A, signing a book deal, or getting accepted into an Ivy League school is not the accomplishment. The accomplishment is on the other side of the blood, sweat, and tears you must pour into your work. The accomplishment is bringing something of your own to life.

The Wright brothers were just a couple of midwesterners running a bicycle shop. What did they know about aviation? Not much at first, but they were driven to learn and build. One of the few locals in Kitty Hawk, John T. Daniels, remarked, “It wasn’t luck that made them fly; it was hard work and common sense; they put their whole heart and soul and all their energy into an idea and they had the faith.”

Embrace the outside track. And once you’ve gained traction, keep a healthy distance. It’s a gift when people are unsuspecting. You free yourself to focus on creating and gain an element of surprise that keeps the competition off guard. Besides, there’s nothing more motivating than when someone has counted you out. That’s right where you want them.