“Knowledge is subtractive, not additive—what we subtract (reduction by what does not work, what not to do), not what we add (what to do).”

On August 6th, 1986, Bob Dylan walked off the stage at Paso Robles State Fairgrounds alongside Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers and he knew he was done. Dylan had one more stretch of shows lined up with Petty the following year—The Temples in Flames Tour—but after that, it was time to hang it up.

It had been 25 years since an unassuming kid from Hibbing, Minnesota showed up in Greenwich Village to immerse himself alongside his heroes in the folk-music community. And it was a legendary run. But Dylan acknowledged the reality of what his fans, critics, and peers had already voiced, his best days were behind him.

Dylan could no longer fill stadiums on his own and had to rely on big names like Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers or The Grateful Dead to draw crowds. He struggled to write new material—not that he had much desire to do so. And despite the hundreds of songs he had written over the course of his career, there were only a handful he would consider playing.

During the Summer tour in 1986, Benmont Tench, the keyboardist in Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers, often pleaded with Dylan to include different songs in the set, like “Spanish Harlem Incident” or “Chimes of Freedom.” Dylan would muster up some excuse or play it off until he was able to divert the attention away from himself.

The reality is that he could no longer remember where most of the songs he wrote came from. He couldn’t relate to or understand how he might even attempt to bring those songs back to life. They were a mystery lost to the past.

Dylan’s plan was to coast through the final tour with the same 20 songs and try to come out unscathed before he went into hiding. That was the deal he made with himself to get through one more run.

The next year before kicking off his final tour with Petty, Dylan was scheduled to play a few shows with The Grateful Dead. He traveled to San Rafael, California to rehearse with The Dead at their studio. After an hour of rehearsal, it was clear that the strategy he used with Petty wasn’t going to work. The Dead were adamant about playing different songs from the depths of Dylan’s catalog. Material he could barely recall.

He sat panicked and knew he had to get out. The Dead were asking for someone he felt no longer existed. During a lull in the rehearsal, Dylan falsely claimed he left something at the hotel. He stepped out of the studio and onto Front Street to plan his escape.

After wandering for a few blocks, Dylan heard music coming from the door of a small bar and figured that was as good of a place to hide out as any. Only a few patrons stood inside and the walls were baked in cigarette smoke. Towards the back of the bar, a jazz quartet rattled off old ballads like “Time On My Hands.” Dylan ordered a drink and studied the singer—an older man in a suit and tie. As the singer navigated the songs, it was relaxed, not forceful. He eased into them with natural power and instinct.

As Dylan listened on, there was something familiar in the way the old jazz singer approached the songs. It wasn’t in his voice, it was in the song itself. Suddenly, it brought Dylan back to himself and something he once knew but had lost over the years—a way back to his songs.

Earlier in his career, Dylan wasn’t worried about the image that others projected upon him, the expectations, or the fame. All he cared about was connecting with the song and doing it the justice it deserved. He was there to bring the words to life—a conduit of sorts. The old jazz singer had reminded him of this simple truth and where to pull from.

Returning to The Grateful Dead’s rehearsal hall, Dylan picked up where he left off like nothing happened. He was rusty and it would take years for him to truly get back to form, but he settled back into a state of relaxed concentration by returning to his principles that were buried underneath all the success, failure, praise, and criticism.

As he continued the final tour with Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers, over the first four shows Dylan played 80 different songs, never repeating a single one, just to see if he could do it. It wasn’t perfect. It wasn’t always pretty. But he was starting to tap back into himself and knew how to reach the music again.

Where am I?

In our own lives, we inevitably reach moments where we feel like we’ve lost ourselves along the way. Where am I? How did I get here? What am I even trying to do? We feel like fragments of our former selves. Exhausted rather than energized by the challenges we face.

Dylan is not alone in his experience. When we lose the connection to ourselves, our work, careers, and lives grow stagnant. We can’t create anything meaningful if we’re absently going through the motions. Gradually, then suddenly we become strangers to ourselves.

As the emptiness creeps in, there’s a temptation to go into hiding. We fixate on our faults and let that feeling wash over us. We lose ourselves in the darkness. And when we get stuck here, we compromise our own integrity and the integrity of our work.

Life is deceptive in this way. We overcomplicate things. We inflate the importance of things that don’t really matter. We lose track of what brings us to life—the things we find deeper meaning in. We let our guiding principles fall out of focus.

In the messiness of life, we make small compromises that add up over time. We say yes to the wrong things and no to the right ones. Things start to pile up. And the more we stack on top of ourselves, the deeper we bury our own priorities. Eventually, the weight of it all drags us down and obscures our vision.

At this point, we can continue adding more, doing more, always saying yes, never saying no, breaking ourselves to meet the expectations cast upon us. We can continue floundering and creating more distance from ourselves. Or we can step back and ask, is this still serving me? What do I need to shed to come back to myself? What’s at my foundation?

Finding our way back

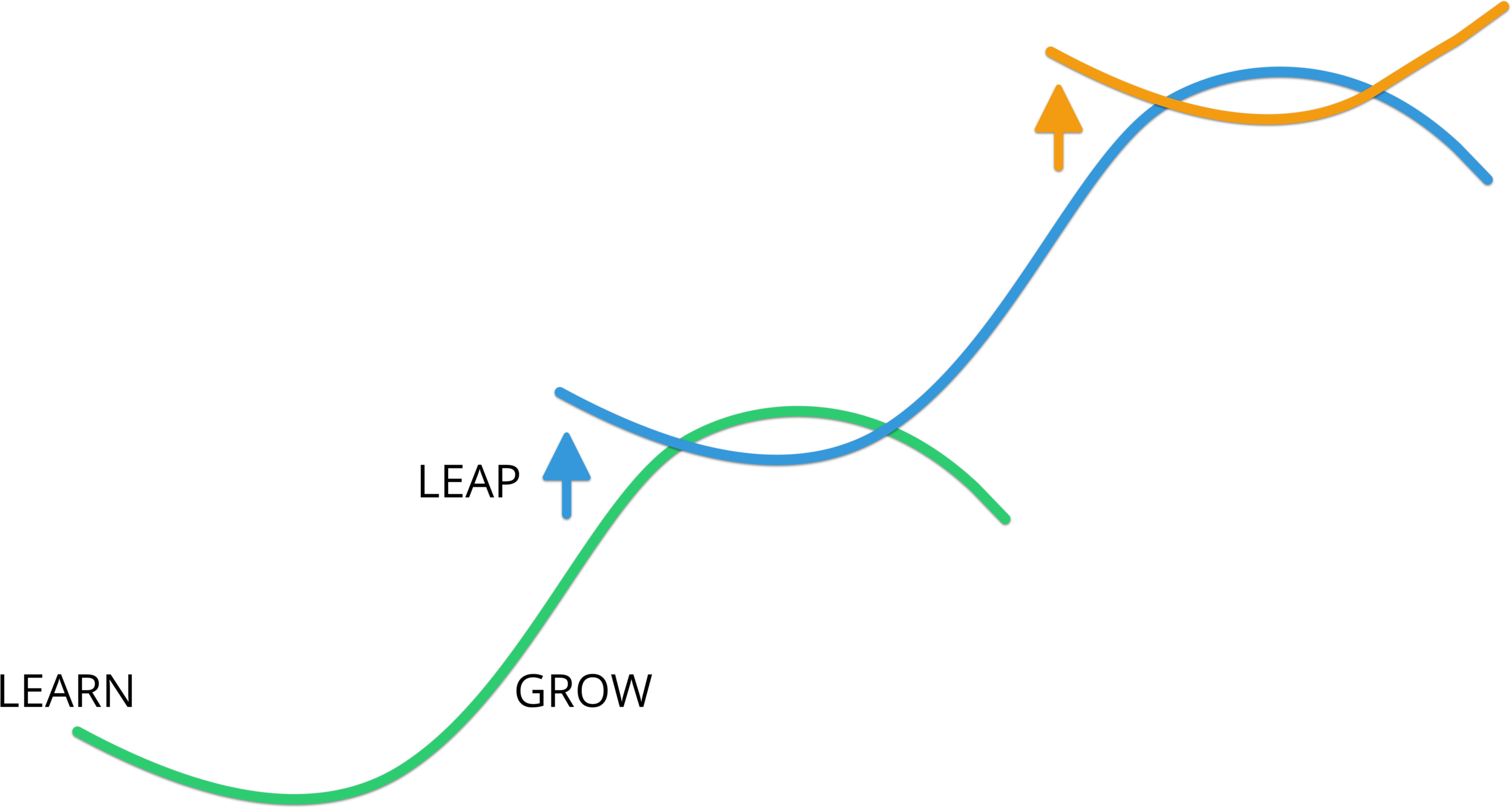

Sometimes the way back to yourself is through subtraction.

This starts with peeling back the layers that have built up over the years.

What’s hidden underneath it all?

What was your original motivation in your work?

What got you here in the first place?

What did you know then that you’ve since forgotten?

What about this once brought you joy?

Finding a way to return to the simple truths we once knew can help us realign ourselves. Our foundation reminds us of what we set out for.

Far too often we attribute our identities to things that are beyond our control. We get caught up chasing what’s external to us because we trick ourselves into believing that’s what makes us who we are. But we are not our jobs, companies, titles, or paychecks. We are not the criticism, praise, accolades, or rejection we face. We exist beyond that.

When we are just starting out, we instinctively understand this. We focus on internals and creating from what we know to be true about ourselves. We build from what inspires us. And that is enough. Because that’s all we really know.

As Dylan faced this struggle, inspiration from an unlikely source brought him back to a beginner’s mindset and the principles he understood early in his career before everything got so carried away. Performing was about reaching for the truth within the song and putting that front and center.

This mindset allowed him to tap back into himself. He was able to once again find meaning in his songs and remember why he was doing what he was doing. He embraced his responsibility to perform each song to the best of his ability.

From this point on, Dylan focused on playing smaller theaters and more intimate shows—drawing songs from every stage of his career, reinterpretations, new songs, and rarities. Returning to the basic truths he lost along the way led to his resurgence as an artist. Rather than signaling the end of his career, The Temples in Flames Tour helped Dylan uncover the start of something new.

Letting go to remember

Connecting back to yourself starts with cutting away the nonessentials and reminding yourself how you found your way here in the first place. Subtract to get to the truth of things.

In the process of letting go, you start to remember who you are and what you find meaning in.

This doesn’t mean you should try to recreate the past. You can’t go back in time. Dylan wasn’t trying to bring a younger version of himself back to life. He was just returning to the principles that set everything in motion and rebuilding from there.

A beginner’s mindset can help you distill the real parts of yourself—the anchors that give you substance and depth. By paring down to what’s real and what’s within your control, you tap back into what sustains you. And as you sift through the rock, dirt, and debris, you free yourself to move with conviction towards bringing your best work to life.