“If you care too much about being praised, in the end you will not accomplish anything serious…Let the judgments of others be the consequence of your deeds, not their purpose.”

Six months after reaching space aboard the Space Shuttle Endeavor, Mae Jemison announced her resignation from NASA. Her childhood dream was fulfilled. And while she wasn’t done with space exploration, she wanted to apply her knowledge, skills, and experience in new ways that would have otherwise been limited by the specialized training of the astronaut corps at NASA.

Many people considered her foolish to leave NASA—why walk away from the pinnacle of human exploration? But she trusted herself and knew it was time to focus on the next thing she found meaning in. This wasn’t the first time she made a decision that challenged the status quo in favor of an opportunity that was meaningful to her.

At 20 years old, after graduating from Stanford with a Bachelor’s in Chemical Engineering and Afro-American Studies, Jemison enrolled in medical school at Cornell. In between semesters, she traveled and found a real sense of purpose in providing primary medical care in developing countries. These experiences taught her more about herself and helped her feel more connected to the world. She immediately knew she wanted a deeper experience in this environment after finishing medical school.

Going against the grain

But the expectation at Cornell—an elite medical school—was that their graduates pursue a prestigious residency after graduation. Jemison simply wasn’t interested. She planned to complete a brief one-year internship at the Los Angeles County/University of Southern California Medical Center. She would then return to work in the developing world to help in whatever capacity she could.

The deans at Cornell weren’t thrilled about her plan. One afternoon, they called Jemison in for a meeting and asked her to reconsider. She explained her reasoning, but they interrupted and claimed she was making a mistake. They outlined the consequences—she would fall behind her peers over the next decade and feel less accomplished. She followed her decision anyway.

After completing her internship, Jemison joined the Peace Corps as a Medical Officer for Sierra Leone and Liberia. She was responsible for the health of all Peace Corps volunteers, staff members, and embassy personnel. She acted as a primary care physician and managed a medical office, laboratory, and pharmacy.

While in West Africa, she navigated environments with insufficient equipment, medication, and supplies. But she honed her resourcefulness, pulling knowledge across different disciplines to navigate challenging situations.

Early in her tenure, one of the Peace Corps volunteers became sick with what Jemison thought could be meningitis with life-threatening complications. She worked to stabilize his condition through the night. But his condition worsened, and she knew she had to act.

Jemison called the U.S. Embassy to secure a military medical evacuation. They questioned whether she had the authority to give that type of order. She calmly explained the situation and that she didn’t need anyone’s permission. The Embassy conceded. By the time Jemison and the volunteer reached the Air Force hospital in Germany, Jemison had been up for 56 hours. But she had saved his life.

These types of experiences would prove invaluable and set her apart when, on her return to the U.S. in 1987, when she applied to NASA’s astronaut training program. Out of 2,000 applicants, Jemison was one of the fifteen accepted.

Almost ten years from the day that the deans at Cornell told her that she was setting herself back in her career by taking a non-traditional approach and that she would regret it, Jemison was orbiting Earth as the first black woman in space.

What type of person are you?

Rather than prioritizing influence or prestige, Jemison was operating from a different place. She was focused on who she was and what she found meaning in. It wasn’t a position that she wanted to define her life. It was the type of person she was.

Jemison found meaning in creativity, exploration, and being helpful. She found meaning in engineering, art, dance, medicine, exploring space, exploring other countries, and exploring new ideas. Above all, she wanted to help and make a difference in the world through the skills and interests that defined her. She channeled this into her work and the opportunities she pursued at each step.

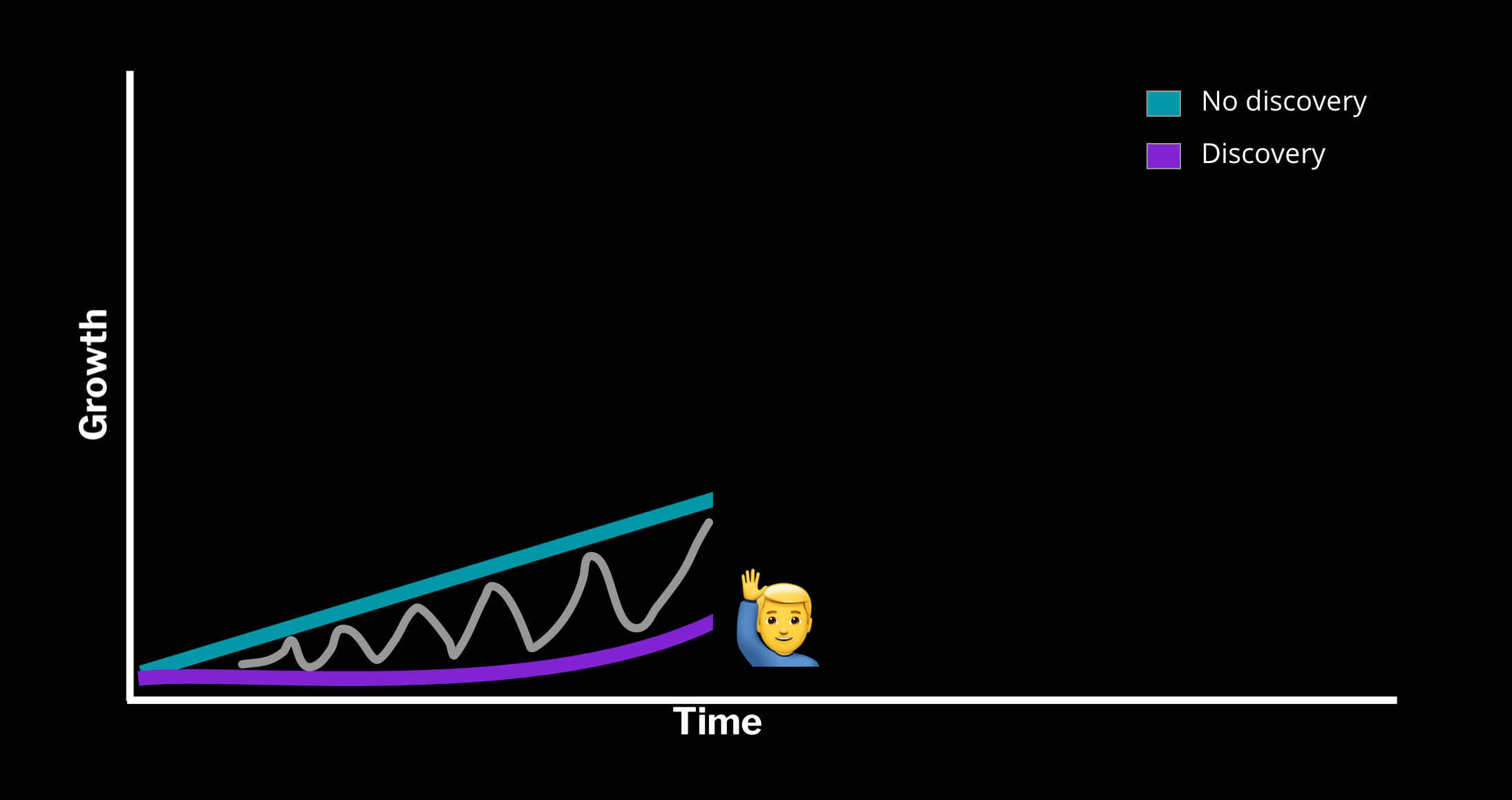

If you focus on work that matters to you and discover significance in yourself, you put yourself in a position to build something that strikes a deeper chord with others.

Influence wasn’t Jemison’s end goal. She approached it with indifference and chalked it up as nice to have but non-essential. Instead, she focused on her character, investing her time in what she found meaningful. She sought meaning over influence at each step of her life.

The desire for influence, like the desire to belong, is human nature. Many people allow this to dictate the course of their lives, often unconsciously. But acting deliberately and purposefully requires a deeper sense of awareness.

If influence acts as your guiding principle, you dull your sense of authenticity and compromise the quality of your work. How effective can your work be if you sacrifice your integrity and sense of meaning along the way?

People gravitate toward those who have discovered a sense of meaning in their work. It just hits differently.

Start with meaning

By focusing on meaning first, there’s a greater chance your life and work will resonate and make a measurable difference in the world. And even if it doesn’t, it remains valuable because it meant something to you. There’s a fundamental beauty in that.

Influence is far more likely to follow if you build something you believe in. And irrelevance is all but guaranteed if you continue to wander the path of least resistance, looking for a quick hit of attention or praise.

Your work must resonate with you before you can expect it to resonate with anyone else. You must fight like hell to ensure your work feels true before you release anything of your own into the wild.

Meaning starts with something that’s all your own. By prioritizing meaning over influence, you build the courage to speak from a place that resonates with you rather than following what other people have deemed important.

It’s a dangerous game to tie your sense of meaning and self-worth to external conditions. You introduce dependencies that can drop you into a state of anxiety, envy, or despair without warning. You allow yourself to be pulled along at the whims of others.

Regardless of the expectations or paths others had followed, Jemison made decisions that optimized for meaning over influence. She trusted her internal compass over any sort of fleeting recognition, status, or prestige.

After NASA, Jemison launched her own company. One of her first projects was to create an international science camp—The Earth We Share—that promoted critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Jemison also started teaching environmental studies at Dartmouth. Eventually, this led her to found 100 Year Starship, an initiative to establish capabilities for human interstellar travel within the next 100 years.

It’s a rare thing in this world to seek significance in yourself and build the courage to create something that resonates with you.

Seek meaning first, and authenticity and influence will follow.

Seek influence first, and you’ll risk losing yourself along the way.