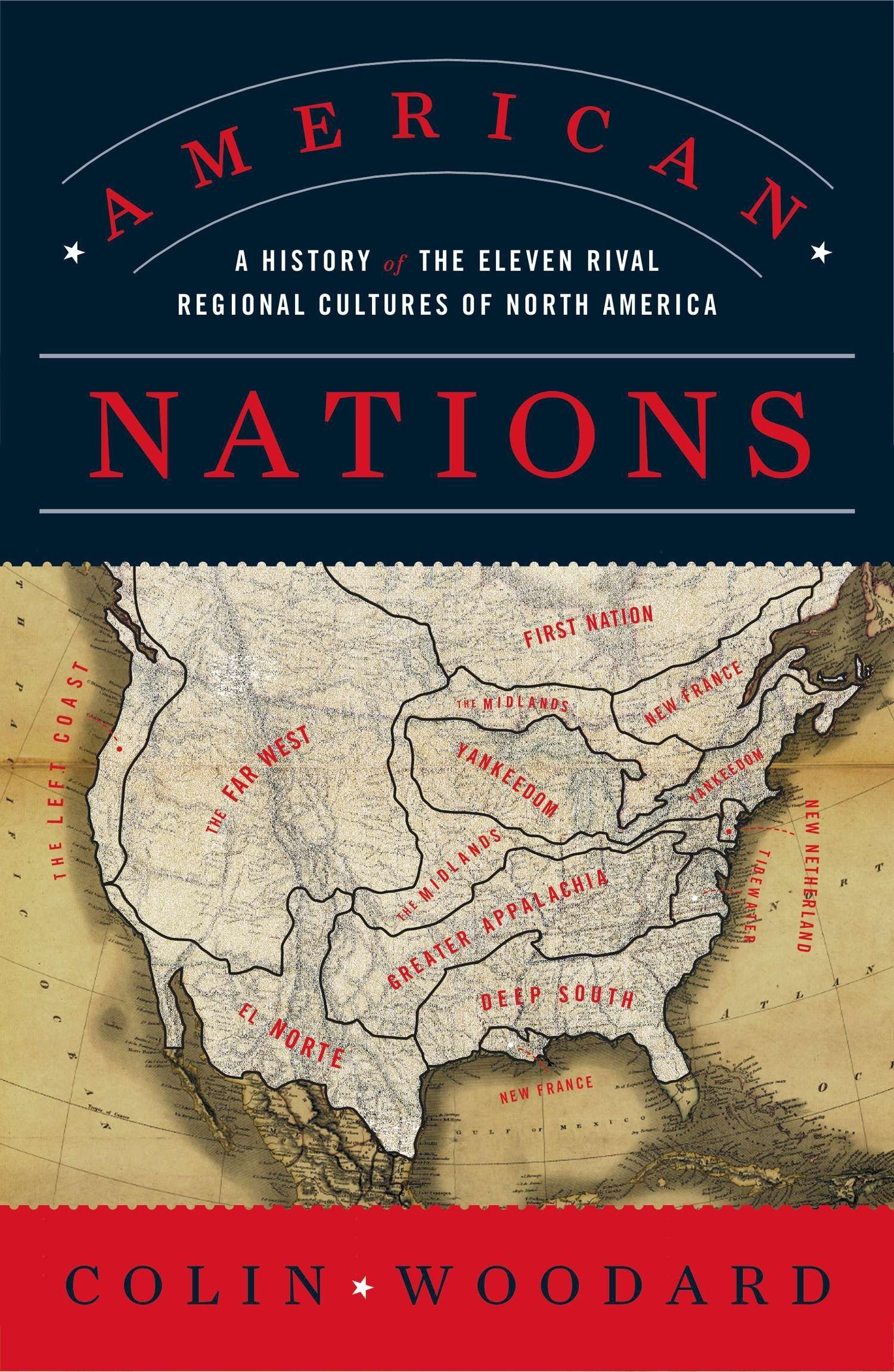

American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America – by Colin Woodard

Recommendation: 8/10. Date read: 7/28/20.

Challenges the perspective that the Americans are living through a uniquely divisive moment in time. Instead, Woodard suggests Americans have been deeply divided since the days of Jamestown and Plymouth. The original North American colonies were settled by people from distinct regions with unique religious, political, and ethnographic characteristics. Since the colonial period, the eleven rival regional cultures in North America have regarded one another as competitors for land, settlers, and capital. Woodard offers insight into why specific regions hold a particular set of beliefs, the power of early influence, and the dangers in blindly adopting ideologies. It’s a powerful book and source of perspective to help you navigate current events without getting trapped into a tribe mentality.

See my notes below or Amazon for details and reviews.

My Notes:

Illusion of Unity:

Americans have been deeply divided for centuries—original North American colonies were settlement by people from British Islands, France, the Netherlands, Spain. Each with distinct religious, political, and ethnographic characteristics. Saw the other as competition for land, settlers, and capital.

“American’s most essential and abiding division are not between red and blue states…the United States is a federation comprised of the whole or part of eleven regional nations, so of which truly do not see eye to eye with one another.” CW

The 11 rival regional cultures: Yankeedom, Tidewater, Greater Appalachia, The Deep South, New Netherland, New France, The Midlands, First Nation, El Norte, The Far West, The Left Coast.

These regional cultures have been fundamental in shaping the way we think, as well as North American history, politics, and governance.

Power of Early Influence:

“Thus, in terms of lasting impact, the activities of a few hundred, or even a few score, initial colonizers can mean much more for the cultural geography of a place than the contributions of tens of thousands of new immigrants of a few generations later.” Wilbur Zelinsky

Goals in each region:

Early Yankeedom and Midlands—building a religious utopia.

New Netherland—individual freedoms of conscience, speech, religion, assembly.

New France—complex network of Indian alliances.

Chesapeake colonies (Tidewater)—recreate the genteel manor life of rural England in the New World.

Greater Appalachia—warrior culture, self-reliant, suspicious of outside authority, valued individual liberty and personal honor above all else.

Tidewater:

“Tidewater’s semifeudal model required a vast and permanent underclass to play the role of serfs, on whose toil the entire system depended. But from the 1670s onward, the gentry had an increasingly difficult time finding enough poor Englishmen willing to take on this role.” Slave traders offered a solution. Slave caste grew from 10% of Tidewater’s population in 1700 to 40% in 1760.

“The south was not founded to create slavery; slavery was recruited to perpetuate the South.”

In the early years, Tidewater was settled largely by young, unskilled male servants.

Yankeedom:

Central myth of American history is that founders of Yankeedom were champions of religious freedom, fleeing religious persecution. Only true of a few hundred pilgrims (English Calvinists) in Cape Cod in 1620. Vast majority were Puritans who “forbade anyone to settle in their colony who failed to pass a test of religious conformity.”

“Early Yankeedom was less tolerant of moral or religious deviance than the England its settlers had left behind.”

Expectation that everyone should read the Bible required everyone to be literate. This led to a proliferation of schoolhouses and requirement that all children be sent to school.

New Englanders always intended to rule themselves so they were never beholden to nobles or corporations.

New England’s colonists were skilled craftsmen, lawyer, doctors. Came over as families. Gave them more of a normal distribution of age and gender ratios than other regions. Allowed their population to grow faster. 1660, Yankeedom population was around 60k (twice Tidewater).

Deep South:

“From the outset, Deep Southern culture was based on radical disparities in wealth and power, with a tiny elite commanding total obedience and enforcing it with state-sponsored terror.” CW

“Most of the other nations were societies with slaves, not slave societies per se. Only in Tidewater and the Deep South did slavery become the central organizing principle of the economy and culture. “ CW

Civil War: If not for Deep Southerners attacks on federal post offices, mints, arsenals, and military bases in 1861, they might have negotiated a peaceful secession. Prior to South Carolina’s militia assault on Fort Sumter, Yankeedom lacked allies in its desire for force. This proved to be the catalyst that mobilized other regions who were previously disinterested coming to the aid of the North.

Greater Appalachia:

Embraced a self-sufficient way of life, living off the land and moving every few years. Life in Britain taught them not to invest too much time and wealth in fixed property which was easily destroyed in time of war.

“When they did need cash, they distilled corn into a more portable, storable, and valuable product: whiskey, which would remain the de facto currency of Appalachia for the next two centuries.” CW

“‘Hoosier’—a Southern slang term for a frontier hick—was adopted as a badge of honor by the Appalachian people of Indiana.

A Common Struggle:

What brought these rival cultures was an effort to preserve their respective, culture, character, and power structure. “They were joined in a temporary partnership against a common thread: the British establishment’s ham-fisted attempt to assimilate them into a homogenous empire central controlled from London.”

By the time England tried to impose uniformity and centralization of power, many of the regions were several generations old and had their own traditions, values, and interests.

Articles of Confederation created more of a political entity (like the EU) that was a voluntary alliance of sovereign states. Not a nation state.

The Left Coast:

Gold rush, 1848: “In what was one of the largest spontaneous migrations in human history to that point, 300,000 arrived in California in just five years, increasing the new American territory’s non-Indian population twentyfold. Within twenty-four months San Francisco grew from a village of 800 to a city of 20,000.”

WW2:

Pearl Harbor united the regions together like never before. Borderlanders fought to avenge attack, Tidewater and Depp South wished to uphold national honor and defend Anglo-Norman brethren, Midlanders backed the war as a struggle against military despotism, Yankees/New Netherlanders/Left Coasters emphasize the anti-authoritarian aspect of the struggle. El Norte and the Far West embraced war which brought resources and investment to their long-neglected regions.

Hitler and Hirohito did more for the development of the Far West and El Norte than any other agent in their histories. Previously they were exploited as internal colonies. But during war were given industrial bases, shipyards, naval bases, aircraft plants, steel mills, nuclear weapons labs, test sites.

Modern Day:

Nations of the Dixie bloc create policies to ensure they remain low-wage resource colonies controlled by a one-party political system which serves interests of a wealth elite. To keep wages low, make it difficult to organize unions. Taxes kept too low to support public schools, urban planning, land-use zoning.

Foreign policy: Yankees = anti-interventionist, anti-imperial, idealistic, intellectual, seek foreign policies that will civilize the world, so they dominate Foreign Affairs Committee. Dixie-bloc = martial and honor bound, aim to dominate and focus on power, so they dominate the Armed Services Committee.

Divergent approaches to economic development, tax policy, and social spending only increase tensions between the cultural blocs.